Almanya‘daki Tatarlar ve Tatar Dili

Tatar diasporası, Almanya, dünya savaşları, propaganda, kimlik inşası

Tatars and the Tatar Language in Germany

Tatar diaspora, Germany, World Wars, propaganda, identity-building,

___

- Cwiklinski, Sebastian (2016). “Germany”. Svanberg, Ingvar & Westerlund, David (eds), Muslim Tatar Minorities in the Baltic Sea Region. Leiden: Brill. p. 159–176.

- Cwiklinski, Sebastian (2014). “Iz istorii tatarskoy pressy i knigoizdatel’skoy deyatel’nosti tatar v Germanii (XX – nachalo XXI vv.)” [From the history of Tatar press and the Tatar publishing activities in Germany (20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries)]. Tatarica 1 (2014), p. 176–181.

- Cwiklinski, Sebastian (2008). “Between National and Religious Solidarities: the Tatars in Germany and Poland in the Inter-War Period”. Clayer, Nathalie & Germain, Eric (eds), Islam in Inter-War Europe. London: Hurst. p. 64–88.

- Cwiklinski, Sebastian (2005). “Po sledam dvukh tatarskikh publikatsiy v Germanii” [Tracing two Tatar publications in Germany]. Gasyrlar Avazy/Ekho Vekov 1 (2005), p. 89–91.

- Cwiklinski, Sebastian (2002b). “Tatars and Bashkirs in Berlin from the End of the 19th Century to the Beginning of World War II”. Güzel, Hasan Celâl; Oğuz, C. Cem; Karatay, Osman (eds), The Turks. Vol. 5. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye. p. 1004–1014.

- Cwiklinski, Sebastian (2002a). Wolgatataren im Deutschland des Zweiten Weltkriegs: Deutsche Ostpolitik und tatarischer Nationalismus. (Islamkundliche Untersuchungen, vol. 243). Berlin: Klaus Schwarz.

- Cwiklinski, Sebastian (2000). Die Wolga an der Spree. Tataren und Baschkiren in Berlin. Berlin: Die Ausländerbeauftragte des Senats von Berlin.

- Dawletschin, Tamurbek; Dawletschin, Irma; Tezcan, Semih (1989). Tatarisch-Deutsches Wörterbuch. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Ersen-Rasch, Margarete I. (2009). Tatarisch. Lehrbuch für Anfänger und Fortgeschrittene. Unter Mitarbeit von Flora S. Safiullina. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Gilyazov, Iskander. (1998). “Die Wolgatataren und Deutschland im ersten Drittel des 20.Jahrhunderts”. Kügelgen, A. von & Kemper M. & Frank, A.J. (eds), Muslim Culture in Russia and Central Asia from the 18th to the 20th Centuries. Vol. 2: Inter-Regional and Inter-Ethnic Relations. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag. p. 335–353.

- Höpp, Gerhard. (1997). Muslime in der Mark. Als Kriegsgefangene und Internierte in Wünsdorf und Zossen (Studien 6). Berlin: Das Arabische Buch.

- Argamak (2021). Website of the Argamak Youth Association (as of 24.01.2021) http://web.archive.org/web/20210124154738/http://argamak.tatar/

- Badretdin, Sabirzyan (2001). “Broadcasting Tatar: My work for the Tatar-Bashkir Service of Radio Liberty.” The Tatar Gazette [online] N4–5, 07-05-2001, Parts I—III.

- http://tatar.yuldash.com/eng_127.html

- http://tatar.yuldash.com/eng_128.html

- http://tatar.yuldash.com/eng_129.html

- Berlin Tatar Youth (2021). https://m.facebook.com/pg/tatar.berlin/posts/?ref=page_internal&mt_nav=0

- Bertugan (2020). Website of the Bertugan Verlag (Bertugan Publishing House) (as of 21.12.2020). http://web.archive.org/web/20210122114116/http://bertugan.de/Startseite

- Diktant (2021). Website of Tatarča diktant Yaz [Competition in Tatar dictation]. https://www.diktant.tatar/

- Hanim (2021). Website of the International Association of Tatar Women “Hanim”. https://tatarhanim.de/

- ICATAT (2021). Website of the Institute for Caucasica, Tatarica and Turkestan Studies. https://icatat.wordpress.com/

- Tatarlar (2021). Website of the Tatarlar Deutschland association. https://tatarlar-deutschland.de/wordpress/

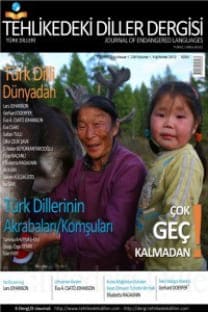

- Başlangıç: 2012

- Yayıncı: Ülkü ÇELİK ŞAVK

Almanya‘daki Tatarlar ve Tatar Dili

Finlandiya‘da Tatarca Edebiyat Faaliyetleri

Sunuş: Tatar Dili Koruma Stratejileri ve Yenilikçi Uygulamalar

Avustralya‘da Tatar Toplumu ve Tatarca Eğitimi

Finlandiya’daki Tatar Dilinin Korunması ve Eğitim Faaliyetleri

Gölten BEDRETDİN, Sabira STAHLBERG

Estonya Tatar Kimlik İnşasında Dilin ve Dinin Rolü

İçindekiler (TDD JofEL 19 Yaz Summer 2021)

Соборная мечеть Санкт-Петербурга в фотографиях и открытках