Estonya Tatar Kimlik İnşasında Dilin ve Dinin Rolü

Bugün Estonya’da 2.000’den biraz daha az sayıda Tatar yaşamaktadır. Bu kişilerin Tatar kimliklerinin temeli dil ve İslam inancıdır. On dokuzuncu yüzyılın sonu ve yirminci yüzyılın başları, Estonya Tatar topluluğu için iyi zamanlardı; çocukların Pazar günleri ve yaz dönemindeki okulları, tiyatro toplulukları ve koroları başkentte ve Estonya’nın diğer kuzeydoğu kasabalarında aktifti. Bu durum, Lutheran ve Estonca konuşulan ortamda benzersiz bir kültürel olguydu: Bir yandan Baltık Denizi çevresinde daha geniş yer tutan Tatar diasporası ile işbirliği yaparken, diğer yandan kültürünü geliştiren, koruyan ve geliştiren Müslüman bir azınlık vardı. Özgünlüğü ayrıntılarda da mevcuttu: Tatar çocukları 1920’lerde coğrafya, din ve dillerini Arap harfleriyle okudular. Narva İslami Cemaati’nin imamı aynı zamanda yerel bir Tatar tiyatro topluluğunun başıydı. 1940’lardan 1980’lere kadar Sovyet döneminde dayatılan duraklamanın ardından Estonya’daki Tatar topluluğu yeniden canlandı. Sovyet öncesi olarak adlandırılan neslin torunları, Tallin’deki Tatar Kültür Derneği’ni ve Estonya İslam Cemaatini yeniden canlandırdı. Ancak Sovyet rejiminin göç politikası Tatar topluluğu içindeki dengeleri değiştirmişti. Din, Tatar kimliğinin temel unsuru olmaya devam etse de, dilin rolü değişti. Bugün Tatar çocukları, Tallin ve Maardu’da Rus dilini ve Kiril veya Latin alfabesiyle yazılan öğretim materyallerini kullanarak din eğitimi almaktadır. Sovyet öncesi dönemden gelen nesil, Tatar dilini ve İslam dinini koruma sorumluluğunu; geçmişi, eğitimi ve deneyimi şimdiden yirmi birinci yüzyıl Estonya gerçeklerini yansıtan yeni nesle devretti. Tatarlarla yapılan kapsamlı görüşmelere dayanan bu çalışma, geçtiğimiz yüzyıldaki dil durumunu tartışmaktadır.

The Role of Language and Religion in Estonian Tatar Identity-building

Today less than 2,000 Tatars live in Estonia. The basis of their identity as Tatars are the language and the Islamic faith. The end of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth century were favourable times for the Estonian Tatar community and children’s Sunday and summer schools; drama societies and choirs were active in the capital and other northeastern towns of Estonia. The activities were a unique cultural phenomenon in the Lutheran and Estonian-speaking environment: a Muslim minority thriving, preserving and developing its culture while cooperating with the wider Tatar diaspora around the Baltic Sea. The uniqueness existed also in the details – Tatar children studied already in the 1920s geography, religion and their own language in Arabic script. The Narva Islamic Congregation’s imam was also the leader of a local Tatar drama society. After the imposed standstill in the Soviet period from the 1940s to the 1980s, the Tatar community in Estonia revived in the 1990s. The grandchildren of the so called pre-Soviet generation restored the Tatar Culture Society and Estonian Islamic Congregation in Tallinn. The immigration policy of the Soviet regime had however changed the balance in the Tatar community. Although religion remains a basic key to Tatar identity, the role of the language is different now. Today Tatar children study religion in Tallinn and Maardu using Russian language and Tatar teaching materials in Cyrillic or Latin script. The generation from the pre-Soviet period has also transferred the responsibility for preserving the Tatar language and Islamic religion to the new generation whose background, education and experience reflect twenty-first century Estonian and European realities. This study is based on extensive interviews with Tatars and discusses the language situation during the past century.

___

- Abiline, Toomas (2007). “Tatarlased Tallinnas 1930. aastatel”. [Tatars in Tallinn in the 1930s] Mäeväli, S. (ed.), Tallinna Linnamuuseumi aastaraamat 2005/2007. Tallinn: Tallinna Raamatutrükikoja OÜ. p. 23–39.

- Abiline, Toomas (2008). Islam Eestis. [Islam in Estonia] Tallinn: Huma.

- Abiline, Toomas & Ringvee, Ringo (2016). “Estonia.” Svanberg, Ingvar & Westerlund, David (eds), Muslim Tatar Minorities in the Baltic Sea Region. Leiden: Brill. p. 105–127.

- Ahmetov, Dajan & Nisamedtinov, Ramil (1999). “Tatarlased”. [Tatars] Viikberg, J. (ed.), Eesti rahvasteraamat. Tallinn: Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 449–450.

- Au, Ilmo & Ringvee, Ringo (2007). Usulised ühendused Eestis. [Religious associations in Estonia] Tallinn: MTÜ Allika kirjastus.

- Iqbal, Maria (2019). Eesti tatarlaste perekonna keelepoliitika kolme perekonna näitel. [Language policy of Estonian Tatar families with the examples of three families]. MA thesis. Tallinn: University of Tallinn.

- Klaas, Maarja (2015). “The Role of Language in (Re)creating the Tatar Diaspora Identity: The Case of the Estonian Tatars”. Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, Vol. 9, No 1, p. 3–19.

- Lepa, Ege (2019a). The Dynamics of Estonian Islamic Community since the Restoration of Independence. PhD thesis. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli kirjastus.

- Lepa, Ege (2019b). “A Time of Change in the Estonian Islamic Community: the question of power among the surrendered ones”. Mjaaland, M.T. (ed.), Formatting Religion. Across Politics, Education, Media and Law. London: Routledge. p. 90–106.

- Lepa, Ege (2020). “The ‘Tatar Way’ of Understanding and Practising Islam in Estonia”. Studia Orientalia Electronica, 8 (2), p. 70−81.

- Loog, Alvar (2017). Eesti Vabariik. Maa, rahvas, kultuur. [Republic of Estonia. Land, people, culture] Tallinn: TEA Kirjastus.

- Ringvee, Ringo (2005). “Islam in Estonia”. Islam v Europe. Naboženska sloboda a jej aspekt. Zbornik referatov z rovnomennej medzinarodnej koferencie. [Islam in Europe. Religious freedom and its aspects. Proceedings of the international conference with the same name.] Bratislava: Centrum pre Europsku politiku. p. 242–247.

- Ståhlberg, Sabira & Ingvar Svanberg (2016). “Sweden”. Svanberg, Ingvar & Westerlund, David (eds), Muslim Tatar Minorities in the Baltic Sea Region. Leiden: Brill. p. 145–158.

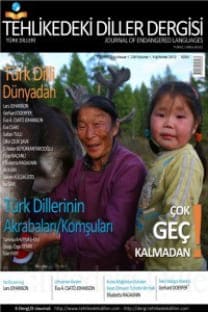

- Başlangıç: 2012

- Yayıncı: Ülkü ÇELİK ŞAVK

Sayıdaki Diğer Makaleler

Tatar Diline Kazandırılmış “Ciñel Tel” Projesi

Finlandiya‘da Tatarca Edebiyat Faaliyetleri

İçindekiler (TDD JofEL 19 Yaz Summer 2021)

Dört Dil Arasında Gezinen Estonya Tatar Aileleri

Avustralya‘da Tatar Toplumu ve Tatarca Eğitimi

Tatarca Kolay Okunan Kitaplar: Dil Öğrenimi, Okuma Geliştirme ve Tehlikedeki Diller için Destek

Sabira STAHLBERG, Fazile NASRETDİN

Tehlikedeki Diller için İnternet Tabanlı Kaynaklar ve Olanaklar

Almanya‘daki Tatarlar ve Tatar Dili

Соборная мечеть Санкт-Петербурга в фотографиях и открытках

Sunuş: Tatar Dili Koruma Stratejileri ve Yenilikçi Uygulamalar